This is a story of lost innocence told through images of Quentino, a young boy growing up in Elsie’s River, a Cape Flats suburb deeply plagued by gang violence. In January, a Grade One pupil of 7 was shot in a gang related incident in Elsie’s River while walking to his first day of school. The exhibition is the product of another long-term project embarked upon by Cape Town based photographer and filmmaker, Gordon Clark. Clark photographed Quentino (‘Tino) over a three-year period in an effort to depict important turning points in his young life. The photographs were taken in a seemingly documentary style, all in Elsie’s River and feature his peers and family. However, one quickly realizes the carefully staged nature of these images; life-defining moments re-imagined and reenacted for Clark’s camera.

Hung as a kind of timeline around the pristine walls of the gallery, we are invited to look in on Quentino’s ‘Groot Geraak’; the all too common progression of innocent young boy to street smart youth adopting the stance, confidence and body language of the larger, dangerous gangster collective. This is a depiction of the terminal choice available to so many Cape Flats children, trying to survive the harsh realities of life in the depths of a gangland – complete coalescence into the gang itself. ‘Tino is taken up into that relentless cycle of violence, that seemingly unstoppable dark force of gangsterism and drugs so prevalent in the area and to which so many local children become cannon fodder.

Clark siphons his compositions through various aesthetic choices; de-saturating and tinting them with a melancholic blue; in order to drive home to the viewer a tangible dilapidation and desperation. Quentino Sleeps next to Bushie and Nallies(2013) is where our porthole onto this world is first punched through. ‘Tino’s innocence and boyhood is underlined here with his childish sleeping pose in stark contrast to the older boy’s (Bushie) more confrontational steely stare into camera. The boy’s heads rest upon a suitcase, a prop placed somewhere within most of the frames exhibited. The use of the repeated image of the suitcase in many ways brings our attention to the fact that these photographs are contrived. Perhaps also it is a symbol of that heavy weight or inherited baggage of the cycle of violence, addiction, repression and prison – a dark legacy handed down through generations of this community. The gang structures of the Cape Flats run deep, and have for decades. Children, often following the example of older family members, or who are recruited to carry out dirty work as a result of their age rendering them too slippery for arrest – join these gangs. They find here in a mutated form, security and acceptance, basic human needs that are so often vacant from their family backgrounds. For ‘Tino and others like him, growing up means acquiring the identity of the larger whole, the gang, an identity that denotes an entrance into manhood, an acceptance into the greater community.

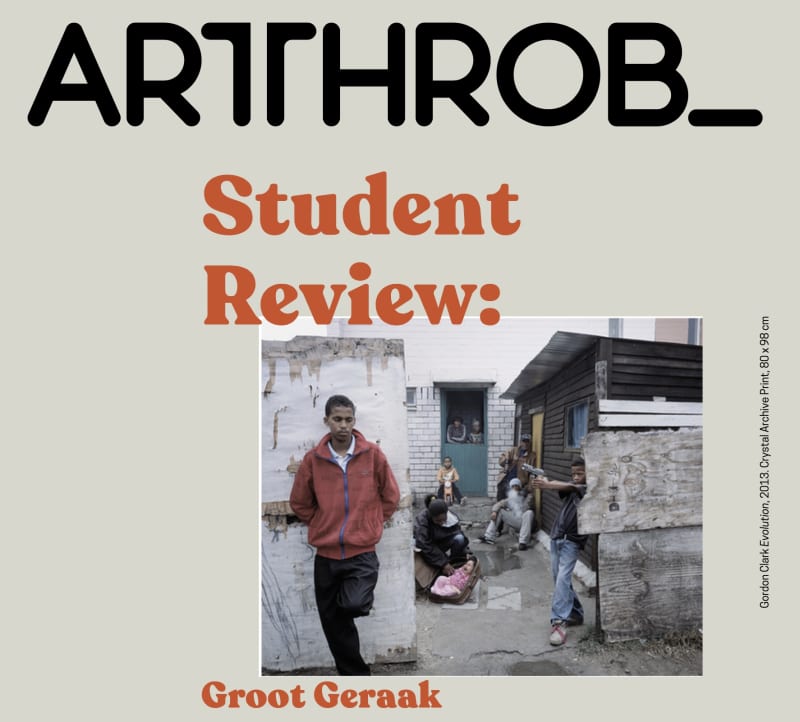

In On the Edge (2013) ‘Tino appears to be lured into the jaws of a shark, a mural painted on the wall that he is uncomfortably leaning against. This moment in the narrative marks that turning point from young innocent, to hawkish and hostile, as depicted through the obvious shift in ‘Tino’s body language, an illustration of his being consumed by the horrifically violent beast that is the gang. A disturbing family portrait, Evolution (2013) has Tino wielding a gun aimed at Bushie whilst the rest of the family looks on blankly. This image is particularly interesting when unpacking the staged nature of Clarks’ work. The players in this scene seem to don props such as a black label beer and smoke billowing from the mouth of one onlooker. The suitcase acts as a cot to a crying baby, an alarming foreshadowing of the fate of yet another innocent borne from, and victim to, this burden of desperate violence. This image especially, when considering Clark’s long career as filmmaker, has an uncanny filmic quality to it. We can understand these tools of staging, as creative tools being used to construct meaning or present the viewer with an allegorical, and thereby firmly Fine Art portrayal of a very real, severe and violent situation.

We are well aware of the countless discourses that accompany such images of the poor and downtrodden, of suffering and tragedy, especially when these images have been beautifully produced, framed, heftily priced and carefully arranged along a pristine white gallery wall. The response is of pity for these children and community, which morphs into frustration and even anger at the photographer and gallery for continuing on this dangerous trend in art; of glamourizing and commodifying poverty and the desperate situation of the other.

However it would be a disservice to the photographer and to those photographed to merely let oneself be swept up by this knee-jerk response. It is important to pause our ‘Sontag-esque’ conversations for a moment, to quieten our minds and to take a closer look at this work. In doing so it is possible to feel the presence of the photographer’s’ well-intentioned humanity; his strong will to depict the harsh reality of a highly vulnerable community, most tragically, the plight of it’s children. In essence the psychological displacement that occurs for all children as they grow up and especially for these children as they enter the battlefield of identity construction – is real.

Clark’s use of overt staging lends his images a hyperreal quality and, it could be argued, is a choice made for the sake of undermining that common media presentation of trauma imagery as real and not framed by a photographer with a political agenda. He is seemingly disassociating his work from those crimes of appropriating and commodifying the image of the other. It is also feasible to perceive the use of hyper-reality as a way of highlighting the performance that is the Cape Flats behavioral language, a physicality that ‘Tino seems to slowly adopt as he is pulled into the unavoidable gang lifestyle.

Similarly, Commune1 gallery in an apparent effort to absolve itself of the transgressions of misrepresentation that go hand in hand with showing work such as this, state in the exhibition’s press release that the show’s success lies in part with the very discomfort we feel whilst looking at these distinctly fine art images in the comfortable space of the gallery. They go on to say that a sense of a shared reality and a shared responsibility for the crisis faced by these children is established. Arguably there is some truth in this, however I am not convinced, and fear that the limited narrative hung on these walls is further distances the child-turned-gangster.

Guests to the exhibition can however page through a photo book of Clark’s ‘Groot Geraak’ project that contains a much larger collection of the images captured during his time with ‘Tino. Broadening the bookends of Tino’s chronicle like this is in some ways a positive step towards the telling of a more complete story. It must be said however, that the adversity photographed, despite its proximity to Capetonian privilege, undeniably exists in another world entirely. These two sides on the reality spectrum are only further wrenched apart when we look onto ‘Tino’s reality as imagined. This sentiment is seemingly encapsulated by the final image on the timeline, a warmer toned picture of a sleeping boy – a return to innocence perhaps, or a depiction of his muted struggle as a mere dream in our minds, as we look upon him from above and far removed.